Black parents, their children and the school hold out against government intransigence

Black parents, their children and the school hold out against government intransigence

In 1979, Mrs Pitt admits her first black student, Nomonde Mtshazo, whose education has been disrupted since the uprising in which she, herself, has taken part. She is later joined by her sister. The daughter of Mrs Selele (the isiZulu teacher) is the first, and at the time only, black child in Grade 1, and her two younger brothers also spend a year in St Mary’s pre-primary.

The trickle of black children entering the school becomes a steady flow in the 1980s. Parents who are intent on giving their children the best education possible are prepared to face the wrath of the government and fury of those among their own people who see them as sell-outs. The school does what it can to make life as safe as possible for the children caught up in these circumstances.

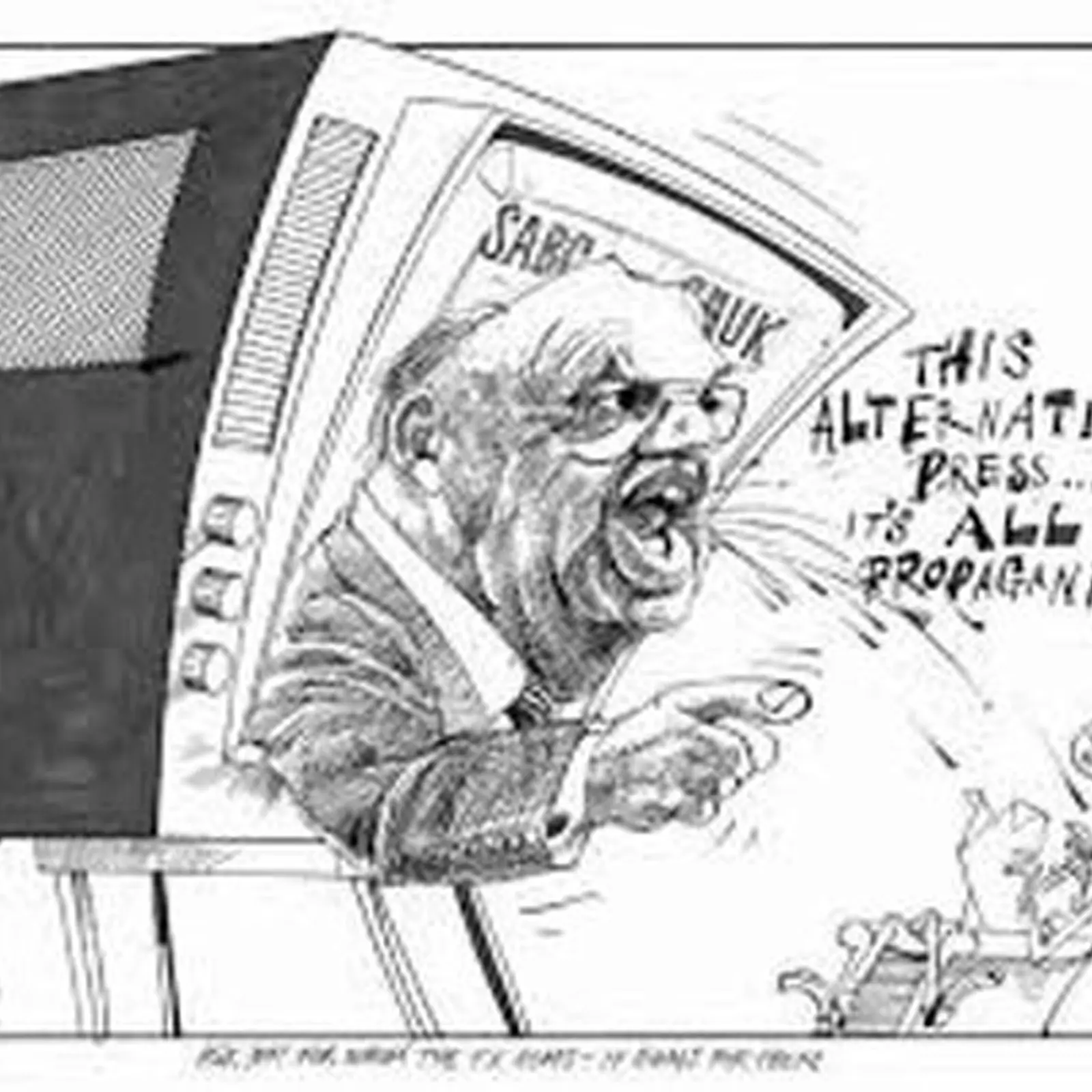

After President PW Botha’s “Rubicon Speech” before the National Party congress, in which, instead of announcing reforms, he does the opposite and digs his heels in, the liberation movements step up the armed struggle, with attacks all over South Africa, including in Johannesburg. A national state of emergency is declared: South Africa is now locked in a low-intensity civil war. Police hit squads kidnap, ambush and murder activists and the ANC responds with brutality of its own.

There are some indications, however, that apartheid is crumbling in the face of defiance. Before the pass laws are scrapped, the ban on mixed marriages is repealed, and the Anglican Church appoints Desmond Tutu as the Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg; he is the first black person to hold a bishop’s post. As Bishop, Tutu is now associated with the school as a member of the Board, and he conducts a number of services in the chapel before he is appointed Archbishop of Cape Town.

A satirical look at P W Botha by the artist Derek Bauer

Anti-apartheid protest in the 1980s

Getty Images

Mrs pitt and her first black pupil, Nomonde Mtshazo, meet after more than 20 years1