From the head's desk: 7 February 2020

Dear parents

The holidays are now a distant memory. So much has happened to confirm, emphatically, that we are back at school: the Grades 5, 6 and 7 girls have returned from tour, the co-curricular programme is well under way, the Grade 7s have been given their leadership roles for the year, and the Grade 4s are preparing to stay overnight at school for the first time at the Senior Primary choir camp this weekend. We also held our first class reps’ meeting of 2020 and it was my great pleasure to welcome Donna Vance, our new Junior School class reps co-ordinator, and her team – which includes four fathers – and to thank them in advance for their assistance.

I took the opportunity last week, in the absence of the older Senior Primary girls, to spend some time alone with the Grade 4s and their teachers: assembly was an intimate, lively affair: a handful of teachers and two classes of girls sang, engaged in informal discussion, and reviewed the first week of the term. The girls spoke about being taught in different venues, sorting out their folders for lessons before and after break, and meeting in smaller mentor groups. Some of them admitted to longing for their old playground; others spoke warily of their encounters with the older girls. The tone was earnest and intent, and I was as aware of the girls who wanted to say something, but didn’t, as those who contributed more volubly to the conversation. I tried to listen, thinking all the time of how we can get better at extending permission to more girls to raise their hands, and keep them raised, when we invite them to offer their opinion.

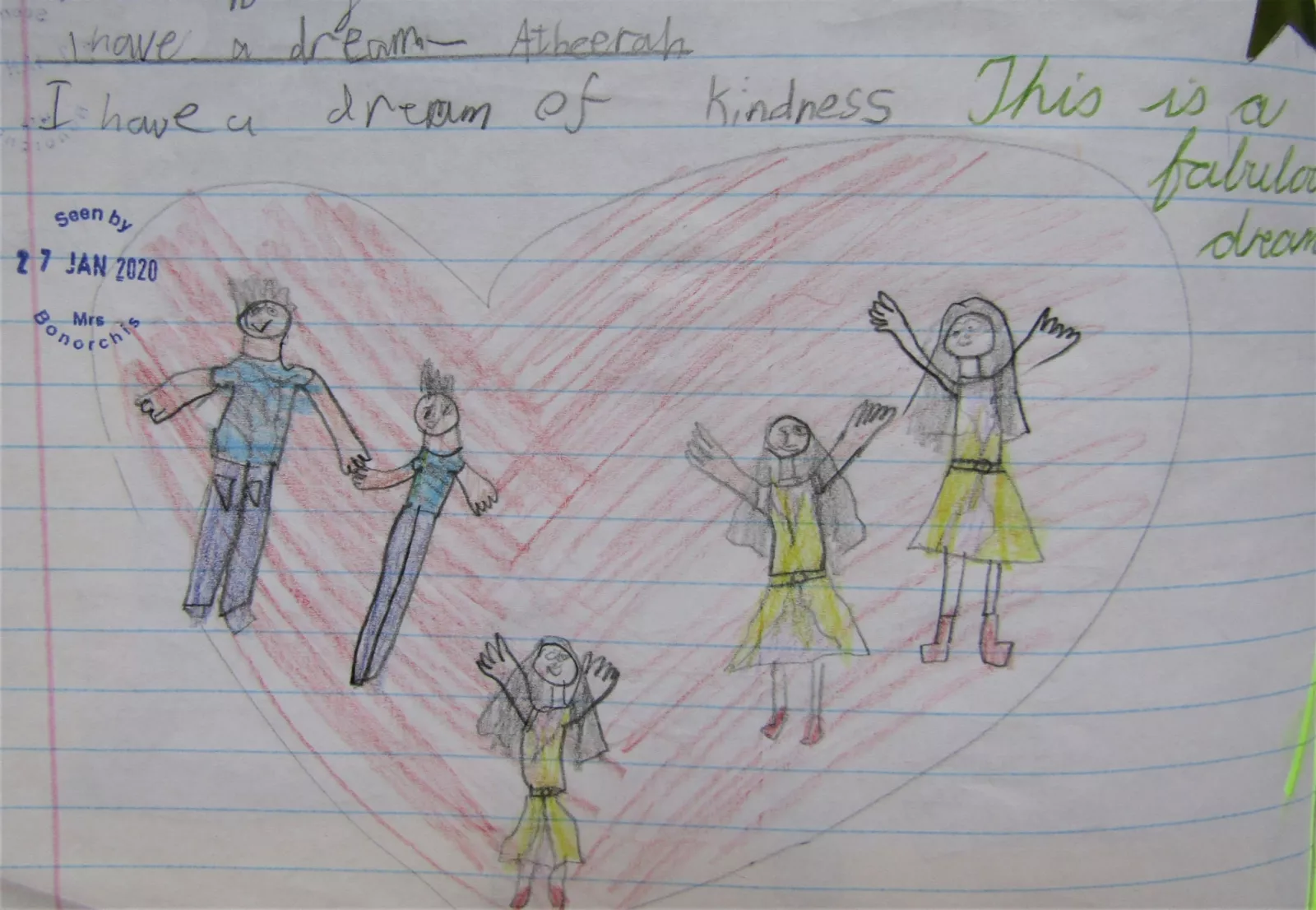

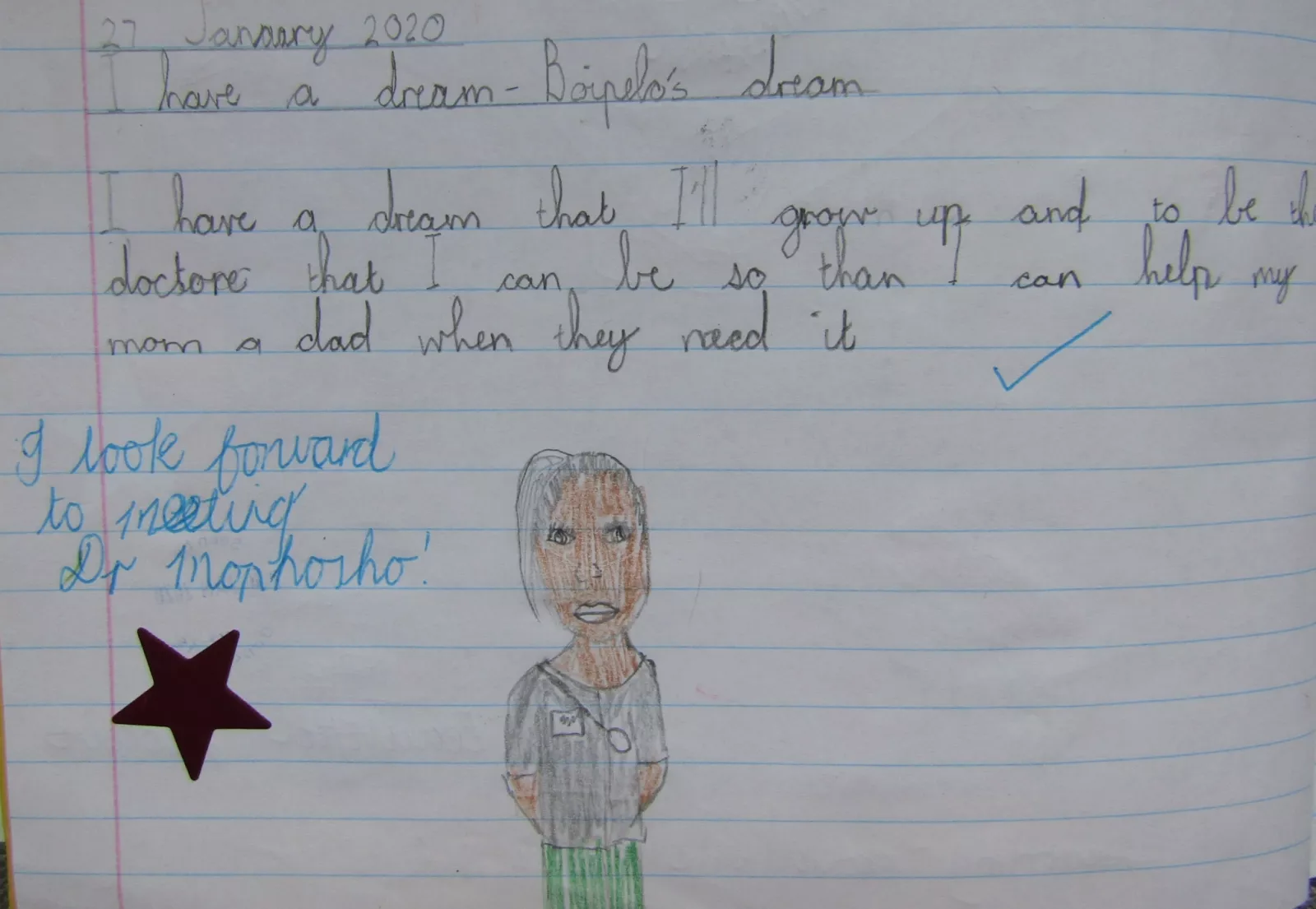

The topic of listening, a popular one among leaders eager to virtue-signal at the beginning of a new year, has been raised several times over the last few weeks. Among the more genuine appeals was the inspiring address given by Steve Moreo, Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg, who spoke about a model of leadership that emphasised the listening ear at headmaster Stuart West’s installation at St John’s College. A fortnight ago, when we acknowledged Martin Luther King Jnr Day in a Senior Primary assembly, I took my lead from a CNN post arguing that King listened his way to greatness. While we remember King’s speeches, the writer observed, we tend to overlook how much the practice of listening, debating and reflecting shaped his career. Often compared to Moses, King, according to Robert M. Franklin Jr., a professor at Emory University, is “more like Socrates. He’s sitting there. He’s asking questions. He’s interrogating. He’s thinking it through. He’s in prayer. He was constantly processing things.”

Real listening, as opposed to the “active listening” practised by enlightened executives everywhere, is hard work. As journalist Emma Jacobs comments in a recent Financial Times book review, “If you are not actually interested in what the other person is saying, it is almost impossible to hear. Curiosity is essential to listening.” Children, as we all know, are especially good at detecting feigned interest; one of the main reasons parents’ perfunctory “How was your day?” is swiftly dispatched with an equally dismissive “Fine” from the backseat of the car. The information that excites parents’ curiosity (“Who did you play with at break?”) is often the last topic children want to explore; conversely, parents and teachers have to work hard at times to remain engaged while children patiently explain some of their more convoluted, if delightful, trains of thought.

Taking an interest in other people and the world around you might just be good manners, but it requires constant effort: so many things militate against it, not least a gnawing preoccupation with the always elsewhere of social media, daily time pressures, and tiredness. (The widespread problem of sleep deprivation is a discussion all on its own.) I know there are techniques, or strategies, to use the preferred term, to improve listening, and I don’t doubt that they work on some level. Actual interest in what another person is saying comes from the heart, though, and involves the kind of radical love of your neighbour that we refer to in our Statement on the Christian identity and ethos of St Mary’s; the kind of love that is the work, and dream (in Martin Luther King Jnr’s expression) of a lifetime.

DR SARAH WARNER

HEADMISTRESS: JUNIOR SCHOOL

Related News

Little Saints News

Grade 0 News

Grade 7 News