From the head's desk: 6 March 2020

Dear parents

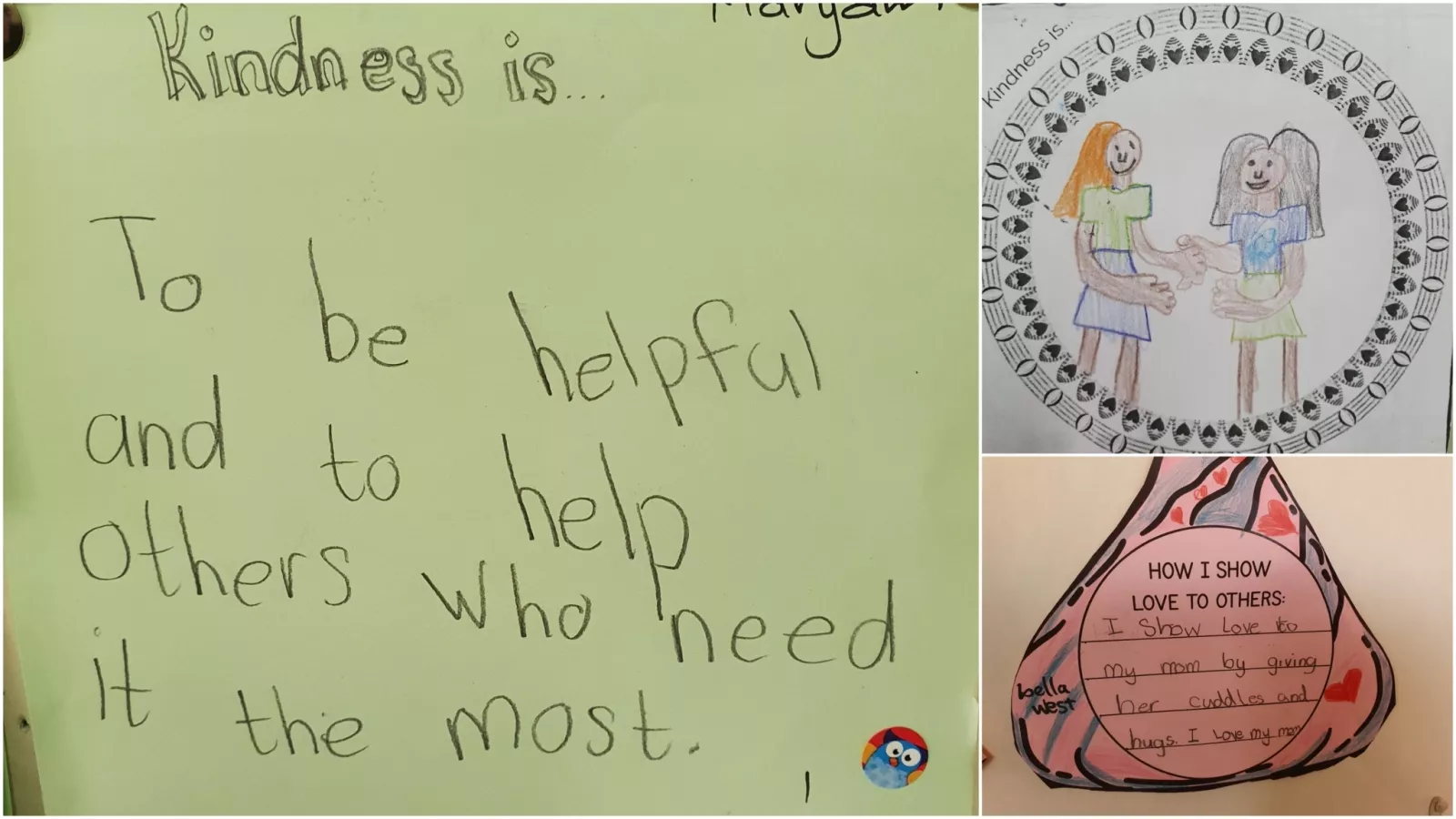

The Junior Primary has chosen kindness as its theme for the term. There’s nothing remarkable in that I hear you say and, no doubt, attendance at class assemblies over the years has convinced you that the concept of kindness in one way or another informs the content of most of these presentations. You’re not wrong, but you’re not altogether right either.

The approach to kindness as a theme across the Junior Primary grades is far more diverse and robust this time around. Each grade is finding its own way through the complex territory of kindness and navigating conversations that point up the differences between kindness and niceness, make plain the practical difficulties of being kind (its social and emotional cost), and that examine the gendered subtext to kindness, its unexciting profile as what psychoanalyst and co-author of the book On Kindness Adam Phillips calls “a virtue of losers” aspired to predominantly by women or, in our context, girls. If kindness has been relegated to the category of essentially feminine practices, it is because it is no longer seen to have much purchase on successful public life. Far better to be self-reliant and assertive (perhaps a form of kindness to oneself?), so the popular zero-sum narrative goes, than kind to others.

Another issue that requires thoughtful negotiation is the difference between adult perceptions of kindness and what the girls see. Teachers might be too quick to commend a child who complies with our expectations of kindness, one who can mimic kind mannerisms for instance, instead of waiting for real evidence of substantively kind acts. To complicate matters further, we cannot assume that the different developmental phases agree wholly on their definitions and impressions of kindness. While they can outline broad behaviours and attitudes that they would recognise as kind, responses to questions on, say, sharing and compromise are bound to differ depending on the age of the peer group being studied.

Last week Thursday, a group of Grade 7 girls hosted the upstander assembly for the Junior Primary girls. They read along to projected images of RJ Palacio’s picture book We’re All Wonders to introduce the themes of empathy and kindness to their younger audience, as well as demonstrating kind behaviour through the dramatization of typical school scenarios. The younger girls responded predictably to prompts from their older peers: they could identify kind and unkind behaviours with ease and their answers to questions were uniformly encouraging, which supports the notion that children are naturally inclined to kindness and open heartedness. Our challenge, as teachers and parents, is how to nourish and sustain this tendency towards benevolence while at the same time engaging with its attendant ambivalence.

For, if we press the younger girls further on kindness, what emerges is a sense that practising kindness can be hard, that being kind to others can make you vulnerable, and that it takes effort and imagination and, frankly, courage sometimes to see it through. If it is the case, as some psychologists and anthropologists maintain, that people are instinctively in sympathy with each other, it is also the case that our competitive social structures do not always support and honour children’s instinct towards kindness. Instead of encouraging our girls to default to the more generalised congeniality or what another commentator calls the “cheery sociability” that passes for kindness in many small American towns, we need to cultivate kindness as a discipline, and rehabilitate it as a demanding virtue requiring our active, deep engagement and constant effort. In Phillips’ words, “… let’s stop the grandiose claims for kindness and instead make simple claims as eloquently as we can: If you’re kinder, more generous, then you’re happier and more imaginative. And the world is better for having you in it.”

Dr Sarah Warner

Headmistress: Junior School

Related News

Little Saints News

Grade 0 News

Grade 7 News