From the headmistress’s desk: 20 May 2019

Dear parents

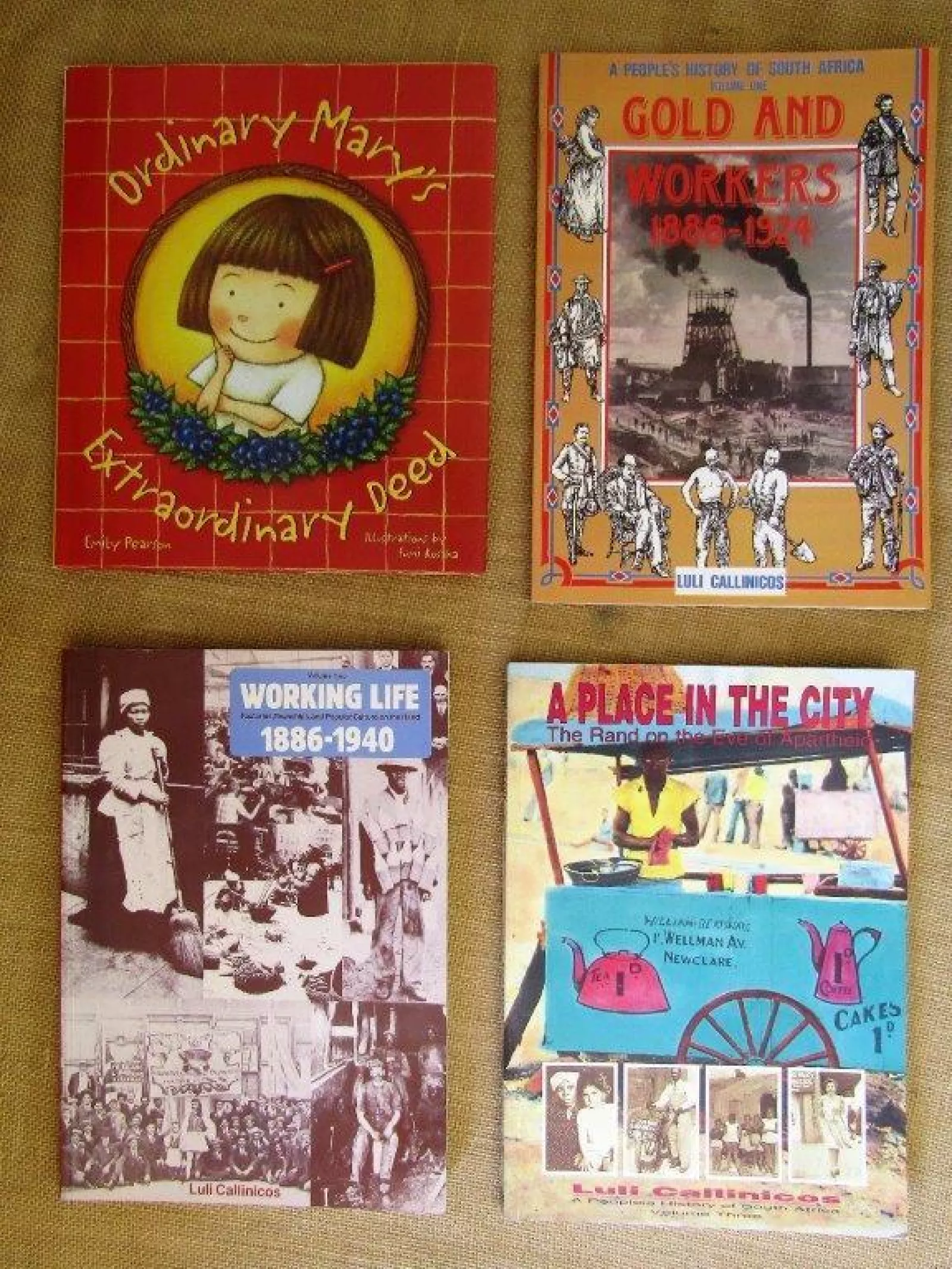

“Ordinary Mary was so very ordinary that you’d never guess she could change the world. This ordinary kid? She did! She changed the world!” So begins the picture book Ordinary Mary’s Extraordinary Deed, which was recommended to me by a Grade 1 pupil in our first assembly of the term. What was startling to me about the little girl’s spontaneous contribution to the assembly was not only the agile transfer of ideas from picture book to abstract discussion that it demonstrated, but also its foregrounding of a child’s ability to engage with dense material on a level that was meaningful to her.

My topic for the assembly a day before elections was, loosely speaking, the value of history from below and the telling of more inclusive stories, especially women’s stories, from the past; the challenge I faced, and which I negotiated with mixed success, was how to enlarge on my theme in a way that an audience of Grade 0 to 7 girls would find stimulating or, at the very least, mildly diverting. Unsurprisingly, the girls and I improvised a solution together.

I began with an anecdote: many years ago, when I was a bit older than the Grade 7s, I entered a school history competition which required all contestants to prepare a speech on an aspect of history relating to the theme “Resistance and revolution”. I entered with a friend (who is now my sister-in-law) and we chose the South African women’s movement as our topic. What made our topic different from many of the other entries was its relative obscurity (other speeches I remember from our first round were on Italian nationalist, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and The Renaissance) and the attendant scarcity of research material on it, including images, in those pre-internet times.

Among the books we consulted, and that would change my ideological presumptions about what made for interesting history for ever, were two of the three volumes on the formation of the South African working class by social historian and founder member of the Wits History Workshop, Luli Callinicos. I pored over the books’ pictures (selected from hundreds of rare photographs of varying quality by Callinicos, with the expert assistance of David Goldblatt) and became completely absorbed in the historical narrative (drawn from interviews, personal anecdote, and other, more official sources) that offered a richly textured account of how and why events unfolded the way they did in 19th- and 20th-century South Africa.

The girls and I spoke about how this approach to history differed from more mainstream research, which tends to focus on the words and deeds of powerful, influential men; the story Callinicos tells reminds us that ordinary people (like the millions of South Africans who would vote, or not vote, the next day) make history. We likened history to a story book and Callinicos’s research to writing that shouts from the margins to draw attention to what has been left out or relegated; we spoke of the incompleteness of stories with certain characters removed from them. One Grade 6 observed that it was like trying to tell a well-known fairy tale while excluding one of the main protagonists. I pushed the analogy further by suggesting that what Callinicos did was teach us to reread the fairy tale with a radically new idea of who or what qualified as a protagonist in the first place. Lastly, we spoke of why it mattered to bring other characters back into the story, whether we needed to keep on looking for opportunities to tell stories differently, and what would happen if we gave up on the work that people like Luli Callinicos began.

We agreed that the world had not changed nearly enough for us to stop actively seeking out other stories: the story of how women came to vote in South Africa, which was different for white women and black women; the story of women all over the world who have been granted the right to vote but are prevented from exercising it; the story of the tiny population of women in the Vatican City who still cannot vote at all. It seemed fitting for me to give the last word to poetry, the repository, in all languages, of some of the most marginal stories on earth.

Famous

The river is famous to the fish

The loud voice is famous to the silence,

which knew it would inherit the earth

before anybody said so.

The cat sleeping on the fence is famous to the birds

watching him from the birdhouse.

The tear is famous, briefly, to the cheek.

The idea you carry close to your bosom

is famous to your bosom.

The boot is famous to the earth,

more famous than the dress shoe,

which is famous only to floors.

The bent photograph is famous to the one who carries it,

and not at all famous to the one who is pictured.

I want to be famous to struggling men,

Who smile while crossing streets,

Sticky children in grocery lines,

famous as the one who smiled back.

I want to be famous in the way a pulley is famous,

or a buttonhole, not because it did anything spectacular,

but because it never forgot what it did.

Naomi Shihab Nye

Dr Sarah Warner

Headmistress: Junior School

Related News

Little Saints News

Grade 0 News

Grade 7 News